Discover the signs, symptoms, and progression of a seizure.

What are the phases of a seizure?

Phases of seizures

Different forms of epilepsy affect people in different ways, and not every seizure has the same symptoms or progression. Because of this, not every individual experiences all of the seizure phases and symptoms we describe below.

A seizure can be composed of four distinct phases:

prodromal, early ictal (aura), ictal, and post-ictal.

Before the seizure

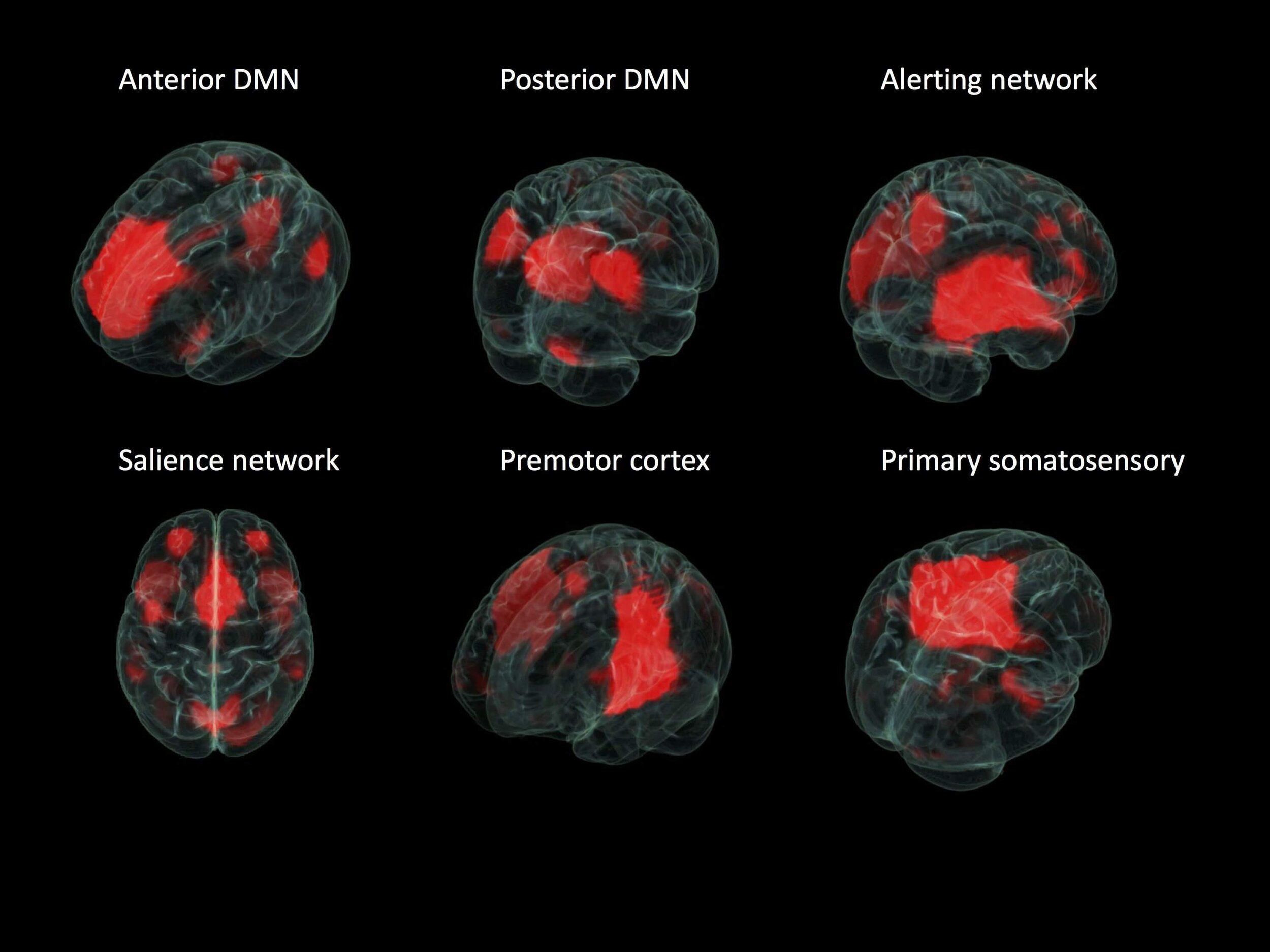

Where seizures start in the brain tells a lot about what may occur during a seizure, what other conditions or symptoms may be seen, how they may affect someone and, most importantly, what treatment may be best for that seizure type. When we don’t know the onset of a seizure, the wrong treatment may be used. Or a person may not be offered a treatment that has the best chance of helping.

About 20% of individuals with epilepsy experience a prodromal phase – a subjective feeling or sensation that can occur several hours or even days before the actual seizure (Besag & Vasey, 2018). The most common symptoms of a prodrome include confusion, anxiety, irritability, headache, tremor, and anger or other mood disturbances (Besag & Vasey, 2018). The prodromal period may serve as a warning sign of seizure onset for those who experience it, but, unlike an aura, this phase is not part of the seizure.

During a seizure

For many people with epilepsy, the earliest sign of seizure activity is an aura. Although it has traditionally been thought of as a warning of an on-coming seizure, an aura is actually the earliest sign of seizure activity and the beginning of the ictal phase. (Besag & Vasey, 2018). The ictal phase includes the time between the beginning (aura, if present) and the end of the seizure.

Like the prodrome (mentioned above), not everyone with epilepsy has auras. For those who do, the specific symptoms vary depending on the seizure type, severity and affected brain region. Some common symptoms include the following:

Vision loss or blurring

Flickering vision

Hallucinations

Déja vu (feeling of familiarity with a person, place, or thing without having experienced it)

Jamais vu (feeling of unfamiliarity with a person, place, or thing despite having already experienced it)

Ringing or buzzing sounds

Strange, offensive smells

Bitter, acidic taste

Out-of-body sensation

Nausea/stomachache

Numbness

Tingling

Dizziness

Head, arm, or leg pain

Subtle arm or leg twitching

Strong feelings of joy, sadness, fear, or anger

An aura can remain localized or progress to other areas of the brain with the person’s awareness becoming impaired to varying degrees. The aura can also spread to both hemispheres of the brain, becoming a secondarily generalized seizure within seconds to minutes after onset (Falco-Walter et al., 2018).

The ictal phase manifests in different ways for every person with epilepsy. They may experience a variety of symptoms, including but not limited to:

Confusion

Memory lapses

Distractedness

Sense of detachment

Eye or head twitching movement in one direction

Inability to move or speak

Loss of bladder and/or bowel control

Pale/flushed skin

Hearing loss

Strange sounds

Vision loss, blurring, flashing vision

Chewing or lip-smacking

Unusual physical activity such as dressing/undressing

Walking/running

Pupil dilation

Difficulty breathing

Racing heart

Sweating

Tremors

Twitching

Arm or leg stiffening

Numbness

Drooling

After the seizure ends

Following a seizure, there is a recovery period called the post-ictal phase. Some people recover immediately, while others require minutes to days to feel like they’re back at their baseline. The length of the post-ictal phase depends directly on the seizure type, severity, and region of the brain affected. Typical symptoms include the following:

Drowsiness

Confusion

Memory loss

Nausea

General malaise

Body soreness

Difficulty finding names or words

Headaches/migraines

Thirst

Arm or leg weakness

Hypertension

Feelings of fear, embarrassment, or sadness

How are different symptoms during a seizure described?

Symptoms

Many different symptoms happen during a seizure. This new classification separates them simply into groups that involve movement.

For generalized onset seizures:

Motor symptoms may include sustained rhythmical jerking movements (clonic), muscles becoming weak or limp (atonic), muscles becoming tense or rigid (tonic), brief muscle twitching (myoclonus), or epileptic spasms (body flexes and extends repeatedly).

Non-motor symptoms are usually called absence seizures. These can be typical or atypical absence seizures (staring spells). Absence seizures can also have brief twitches (myoclonus) that can affect a specific part of the body or just the eyelids.

For focal onset seizures:

Motor symptoms may also include jerking (clonic), muscles becoming limp or weak (atonic), tense or rigid muscles (tonic), brief muscle twitching (myoclonus), or epileptic spasms. There may also be automatisms or repeated automatic movements, like clapping or rubbing of hands, lip-smacking or chewing, or running.

Non-motor symptoms: Examples of symptoms that don’t affect movement could be changes in sensation, emotions, thinking or cognition, autonomic functions (such as gastrointestinal sensations, waves of heat or cold, goosebumps, heart racing, etc.), or lack of movement (called behavior arrest).

For unknown onset seizures:

Motor seizures are described as either tonic-clonic or epileptic spasms.

Non-motor seizures usually include a behavior arrest. This means that movement stops – the person may just stare and not make any other movements.

What if I don’t know what type of seizures I or my loved one have?

It’s not unusual that a person doesn’t know the type of seizure they have. Often seizures are diagnosed based on descriptions of what an observer has seen. These descriptions may not be complete. When seizures are difficult to diagnose or seizure medicines are not working to stop seizures, talk to your doctor or treating health-care provider. Seeing an epilepsy specialist or having an evaluation at an epilepsy center can help you explore other treatment options, such as surgery, devices, dietary therapy, new or add-on seizure medications, or a clinical trial.

An appointment with a neurologist or epilepsy specialist may be needed. An MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan to look at the brain and EEG (electroencephalogram) tests to record the electrical activity of the brain can be very helpful tools in diagnosing types of seizures and epilepsy properly.

Keep asking questions so you get the right tests and right treatment for your type of seizures and epilepsy.

When a disorder is defined by a characteristic group of features that usually occur together, it is called a syndrome. These features may include symptoms, which are problems that the person will notice. They also may include signs, which are things that the doctor will find during the examination or with laboratory tests. Doctors and other health care professionals often use syndromes to describe a person's epilepsy.